Edsel’s Song

| Accessible Plain Text Transcript

Decolonized Sonic Composition

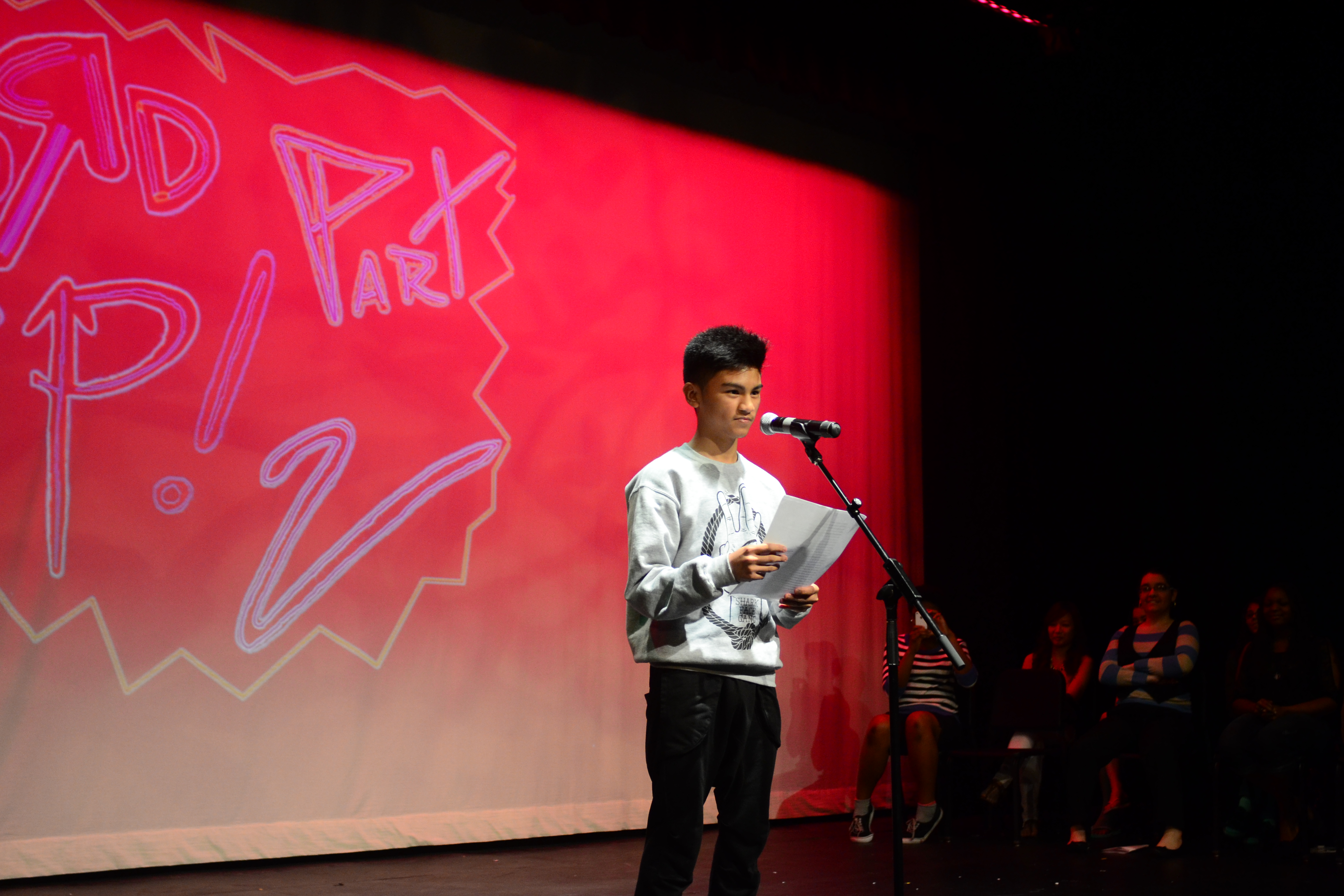

When I first met Edsel, he was a quiet and reserved freshman in high school. In my earlier work (Mooney, 2016), I described his transformation into a poet who moved crowds and inspired us with the power of his words. When we looked back on those experiences together for this study, we seemed to move through time, discovering versions of ourselves that no longer exist. I pulled up photos and videos of him performing in high school, which transported us back to that space emotionally, visually, and sonically. After we reflected on our experiences with Hip Hop and spoken word poetry, I invited Edsel to co-construct a song with me, choosing samples and creating a sonic palette that was meaningful to him—one which he felt accurately reflected his experiences. This track exemplifies how collaborative composition and co-sampling can function in sound-based research.

Edsel is a Filipino American from Jersey City, New Jersey. During our conversations, he talked about his cultural heritage with love, appreciation, and gratitude. He described his personal relationship to Hip Hop and reflected on the Filipino American experience, questioning the impact of Spanish colonization and what that means for him as a person living in the United States who identifies with Hip Hop culture. He shared that our work in the slam poetry club and Hip Hop Lit class, particularly the ways we cultivated knowledge of self, helped him become interested in learning more about his home country, its history, and its relationship to the United States. Edsel expressed his passion for learning about the Philippines prior to Spanish colonization, which prompted us to look for sounds that spoke to the Indigenous cultures and histories of the Philippines.

After the interviews and focus groups, we looked for samples together by sending each other YouTube videos and songs that reflected themes we discussed. Edsel recommended that we sample a Kundiman song, which he described as Filipino love songs. He explained these as traditional serenades that originate from the period when the Philippines was being colonized. Edsel explained that usually a love song is addressed to an individual romantic partner, but these songs actually read as love songs written to the Philippines homeland itself. One of the main vocal leads in this track samples from a Kundiman song. Another important sound we included is a vocal chant from the T’Boli tribe of the Philippines. The T’Boli are one of almost 100 tribal groups in the Philippines. These are decolonial sonic citations—what we might call “counter-samples.” Lastly, Edsel communicated that he would like the song to have a “Lofi” aesthetic, which is a genre of Hip Hop that includes vinyl-sounding distortion and effects that produce a warm, grainy aesthetic.

The Sounds of Homeplace

What is home? Is it a physical place? a community? a metaphor? What does home sound like? Much of Edsel’s poetry, both old and new, explores this question and connects to his reflections about Filipino American identity. If we consider bell hooks’ (1990) concept of homeplace, which she theorizes as a site resistance, refuge, and healing, where individuals and collectives can recover wholeness, then how did the Hip Hop and spoken word learning community that we constructed together function as homeplace? Edsel’s poetry, particularly his declaration that “we will build home / from home,” inspired me to think about the ways we can cultivate homeplace communities in our schools and how those spaces stay with us as models of what’s possible when we “build homes” / or families / or classrooms / from radical love, belonging, and community care. Edsel’s poetry helped me to re-see our youth poetry slam from new angles and perspectives that dislodged and relocated my previous understandings.

Relocation is a phenomenon that is deeply connected to identity, diaspora, and immigration. When Edsel calls us to “reverse / a story / a narrative / the truth of our arrival,” this is what I hear:

the sample plays in reverse as it spins backwards.

I see and hear commercial airplanes

flying backwards through the sky,

landing at their place of origin.

ships sail backwards against the trade winds.

ancestors come back to life while children get un-born.

we see the shoreline, once close enough to touch,

disappear across the horizon

as we sail backwards toward a homeland.

(Re)Searching for Ourselves

The retrospective nature of this project provided ways of looking, seeing, and hearing that extend beyond a fixed location in time and space. My collaborators and I traveled together. We voyaged and journeyed. We arrived back to a place that was altogether different from where we started more than ten years ago. When I showed Edsel a video of him performing a poem on stage as a teenager, he expressed that “I haven’t seen myself that brave in a long time.” I was struck by the emotion in his voice when he talked about what it was like to re-experience “memories and feelings I haven’t really explored in a long time.” In these moments, I wondered about the nature of retrospective research and what happens when we invite participants to hear artifacts of their past.

I also wondered what it means to embody knowledge, to call it forth not only from the schema of our memories, but from the spaces and places that exist in our bodies. Perhaps some memories go dormant. Others are lost altogether. But as Edsel and I talked about this (re)membering, this putting back together from fragment and sample, I thought about how sound, image, and video enabled us to immerse in the (re)membering more viscerally. In this sense, sound becomes an effective method for prompting individuals to travel into a memory or experience.

When I asked Edsel what he still carries with him from the past and into his young adulthood, he responded with “the courage and bravery to still write,” despite the lack of connection to an artistic community. Most of my collaborators described feelings of pride for the younger versions of themselves, teenagers who got up on stage in front of their peers and shared deeply personal poems. This “bravery to still write” can be heard in a new poem that Edsel shared during one of our interviews. In the piece, he plays with the word “flip,” sometimes using it in the context of “flippin back” or “flippin a record over to the B side,” but also as a double entendre that rejects the term as a derogatory slur for Filipinos. He “reclaims” the word here and bends it into shapes that he gets to author with his own voice and agency.

Music producers and beatmakers often use the term “flip a sample” to describe the process of taking the old and transforming it into something new. In this webtext, we flipped samples of experience and remixed them into new research texts that center sound as the primary method of discovery.